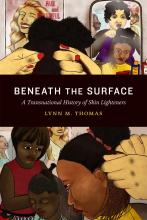

Department of History professors Lynn Thomas and Adam Warren published new books dealing with histories of health this spring. Thomas’s Beneath the Surface: A Transnational History of Skin Lighteners (Duke University Press, 2020) investigates the history of skin lighteners in global popular culture—their use, their sale, and opposition to them from medical professionals, consumer health advocates, and antiracist thinkers and activists. Baptism through Incision: The Postmortem Cesarean Operation in the Spanish Empire (Penn State University Press, 2020), co-edited by Warren, examines medico-religious manuals and guides on cesarean operations composed by Spanish priests in Peru, Mexico, Alta California, Guatemala, and the Philippines beginning in the mid-eighteenth century.

Both books interrogate how colonial structures and local beliefs have intersected with ideas of health and gender and how they circulate globally. Thomas achieves this through a history of cosmetics, while Warren and his co-contributors provide critical context for colonial texts on religious and medical practices around reproduction and childbirth.

“As in other parts of the world colonised by European powers, the politics of skin colour in South Africa have been importantly shaped by the history of white supremacy and institutions of racial slavery, colonialism, and segregation,” wrote Thomas for The Conversation. “During the era of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, skin colour and associated physical difference were used to distinguish enslaved people from free, and to justify the former’s oppression. Colonisers cast melanin-rich hues as the embodiment of ugliness and inferiority.” People living within this racist political system sometimes looked to skin lighteners in order to whiten and lighten their complexions, making skin-lightening creams some of the most popular cosmetics in the world by the twentieth century.

While people around the world have used skin-whitening cosmetics to cover blemishes and smooth the appearance of their skin for millenia, Thomas describes skin lighteners as different. The purpose of a lightener is to remove blemishes or the darkening effects of the sun produced by melanin. The active ingredients in these skin lighteners tend to be harmful, Thomas explained, ranging from lemon juice and milk to sulfur, arsenic, and mercury. Mercury in particular produces damaging physical and environmental effects, leading many countries to ban its use in cosmetics in the 1970s and 1980s. By that point, however, hydroquinone had replaced mercury as the active ingredient in numerous products, and the sale of lightening creams continued.

Advertisements were crucial sources for her research, Thomas told Nastassia Arendse in an interview for the South African Broadcasting Corporation, and helped her trace not only where skin lighteners were sold but also who the target audiences had been. Primarily associated with women of color today, newspaper ads in Capetown and Johannesburg from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries revealed that producers aimed to reach white women with promises to remove freckles. Over time, companies advertising their creams in South Africa found a larger audience among young black women.

“For black and brown consumers, living in places like the United States and South Africa where racism and colourism have flourished,” described Thomas, “even slight differences in skin colour could carry political and social consequences.” Such pressures made apartheid South Africa one of the centers of the global trade in skin lighteners and motivated Thomas to research the subject. “Yet, racism alone cannot explain skin lightening practices,” she stated. In writing Beneath the Surface, Thomas also confronted intersecting dynamics of class, gender, standards of beauty, and the growth of consumer capitalism.

Baptism through Incision likewise provides readers a lens through which to analyze a complex topic entangled with a wide range of historical and contemporary issues that spanned political boundaries and continents. The book is built around a translation of Guatemalan priest Pedro José de Arrese’s 1786 treatise on priests’ duty to perform cesarean operations on recently deceased pregnant women. Arrese recommended that priests extract the fetus before it died with the goal of “cleansing” the unborn child of original sin through baptism regardless of whether or not the fetus would survive. According to Warren, “While the text may focus on a peculiar topic, it speaks volumes about the nature of colonial society in Guatemala and elsewhere during the final decades of Spanish rule.”

The text’s question-and-answer format, Warren explained, “reads as a dialogue that engages a whole range of medical and theological questions about life, death, surgery, duty, sin, and salvation that were pressing issues in the late eighteenth century.” The variety and ambiguity Arrese and writers like him used to describe a fetus versus a baby, for example, was both striking and revealing:

In modern English, we make very stark distinctions between the idea of the “fetus” as inhabiting the womb and the “baby” existing outside the womb. In eighteenth-century Spanish, the term for fetus, “feto,” could refer to both, as could the term “criatura,” which translates literally into English as “creature” but is equivalent in modern Spanish to “child” or “infant.” In eighteenth-century Spanish, this was not the case. A “criatura” could be a fetus, a baby, an infant, or a child.

Arrese’s vocabulary was reflective of and contributed to the conversations he and his fellow priests were having about reproduction, childbirth, life, death, surgery, and salvation.

Baptism through Incision was Warren’s first major collaborative research project, completed with co-editors Martha Few and Zeb Tortorici as well as translator Nina Scott. Warren met Few while working on his first book and an article about postmortem cesarean operations for the purpose of fetal baptism based on a text unrelated to Arrese’s. Few was busy researching a related subject in colonial Guatemala. “We ended up presenting on panels together and becoming good friends,” he divulged, “and we developed a friendship as well with Zeb Tortorici. Both Martha and Zeb consulted Arrese’s text for different reasons in their work, and in 2013 the three of us agreed to work together on its translation and publication.”

Warren and his co-editors designed and wrote Baptism through Incision as a text for undergraduate teaching. In Warren’s words:

[The book] forms part of a series, the Latin American Originals series through Penn State University Press, that focuses on the translation and dissemination of less commonly known primary sources from colonial Latin American and Spain. . . . Ours is a text that will be of interest for courses on the history of colonial Latin America, the history of medicine, the history of reproduction and childbirth, and the history of gender and sexuality in Latin America.

Their aim, Warren stated, was to “create a volume that spoke not just to Arrese’s work and the context of its production in colonial Guatemala, but also to the larger production of texts and the practice of the cesarean operation across the Spanish Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.”

In the course of the research, Warren discovered a love for translation. “I also realized that I really enjoy the challenge and complexity of translation, so much so that I ended up translating the majority of the sources found in the second chapter,” he shared. “I learned a lot about translation in this project, even though I’ve engaged in translating materials for pretty much every piece of scholarship I have published over the course of my career.”

Even so, translation presented some of the most difficult work of the project:

I am grateful to have had the chance to work with Nina M. Scott, who translated Arrese’s treatise and met with us at the John Carter Brown Library for two weeks to study and review it together. Although published in 1786, the original text itself is written in quite difficult and unusually convoluted Spanish—Arrese was not at all a good writer—and it involved navigating many confusing and archaic passages, some of which even required consulting with specialists in medieval Spanish!

Other translations included in Baptism through Incision include an account of the performance of a cesarean operation on a living woman in Spain in 1753, instructional materials for midwives in Mexico on the cesarean operation and baptism, newspaper accounts of the cesarean operation’s use in missions in Mexico and Guatemala and in a city in Argentina, calls for the practice of the postmortem cesarean operation in response to wartime accounts of the killing of pregnant women in the Peruvian Andes, and instructions for performing the operation that circulated in the missions of California.

Warren and his co-editors look forward to editing another book that will incorporate an even wider range of translations. “Although we were unable to include materials from the Philippines, we recently secured a translation of a manual published in the Philippine language of Cebuano, which we will include in our next book,” he shared. “We have also found materials in Tagalog.” Readers and students in Warren’s HSTCMP 247 course on the history of global health next fall have a great deal to which they can look forward.