We recently caught up with PhD student Jess Cavalari, who is on a five-month research trip to Seville in southern Spain. With support from the David and Helen Pinkney and Costigan fellowships, as well as the Antoinette Wills Endowed Fund for Graduate Students through the UW College of Arts and Sciences, Jess is spending their days in the General Archive of the Indies looking for traces of the mule trains of sixteenth and seventeenth-century colonial Panama. In their research, Jess argues that the mule train crossing the Isthmus of Panama, connecting the Pacific to the Atlantic, was as central to the early modern economy of the Spanish Empire as the Panama Canal is for today’s global trade. We met on Zoom, but our conversation took us on a virtual journey through the streets of Seville, to the archives, and into Spanish colonial Panama.

Our conversation started by asking Jess what insights they are gaining from their trip to Spain. What would be lost if all the archives were digitized and accessible online?

Jess says that by physically being in Seville, they gain a deeper understanding of the Spanish empire and its bureaucracy. “This is my first trip to Europe and I have never before been in a city with so many visible layers of urban history.” Walking through the city, Jess discovers traces of Islamic and even Roman Spain hidden in the architecture all around. When the Visigoths conquered the Iberian Peninsula in the fifth century, they used Roman pillars in their construction of new buildings, and when the region became a part of the Islamic Empire in the eighth century, those same columns were reused and integrated into the marvelous structures of Al-Andalus.

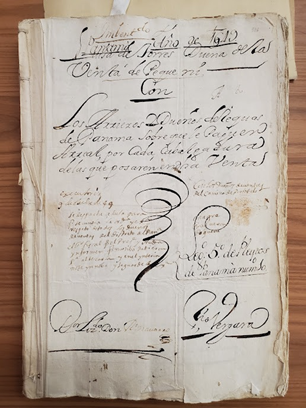

Jess spends many hours each day at the Archive of the Indies, which contains documentation of Spain’s colonial conquest and empire building in the Americas, with the oldest papers going back to the fifteenth century. Seville once held a monopoly on trade with the Americas, and in 1785, its old merchant house became the repository for the paperwork, letters, and court documents that had been sent back and forth across the Atlantic. It is in this same building that Jess sits holding documents in their hands that are more than 300 years old. “The documents are all bundled up, tied together with string, and I really like untying and busting them open. And I love the process of putting everything back together when I am done reading and taking pictures.” So far, Jess has taken over 6,000 photos, which amounts to around 12,000 pages of documents. That is a lot of material to read through and translate once back in Seattle! While they meticulously took notes over each document in the beginning, with time, Jess has developed a sense for the material and has gotten much faster at working through a file. They also benefited from a recent archival policy shift with regard to taking photographs. Initially, researchers were only allowed to take around 50 pictures a day at a special location after archivists had approved the selected documents for reproduction. “Then I come back to the archive one day and suddenly everyone is taking pictures at their desks. I wanted to warn them that they would get into serious trouble, when I realized that the archive changed its rules. Now I can take as many pictures as I want!”

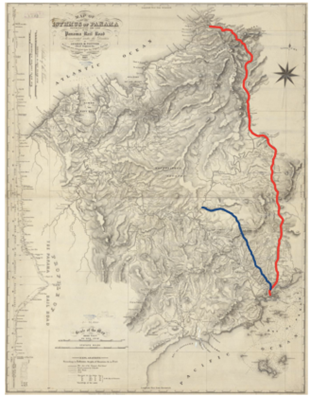

The most exciting documents that Jess found so far concern a series of court cases between the owners of the mule trains, the merchants, and the people who loaded cargo onto the animals. Ships from Europe crossed the Atlantic carrying wine, olive oil, cloth, and clothes. They unloaded their wares at the port of Nombre de Dios and, later, Portobello. From there, the goods were transferred to mules, which would cross the strip of land between the oceans. The Camino Real, or Royal Road, led them for 30 miles through the mountains until they reached Panama City on the Pacific coast. There, the merchandise was loaded onto ships destined for Peru. On the way back, the mule trains transported silver bound for Europe.

The mule train formed the central point of connection for Spanish imperial commerce, linking the Pacific coast of South America and the wider Pacific world of the Philippines to the Atlantic world and Europe. The series of court cases being examined by Jess span the period of 1599 through 1648, in which the owners of mules complained that merchants and packers loaded too much weight onto their animals. “They regularly exceeded the allowed 8.5 arrobas (230 lb.) and worked the mules to death!” Jess also looked at court cases involving the operators of ventas, resting places along the Camino Real where people and mules could rejuvenate while traveling. They regularly argued as to who was responsible for providing food for the mules. Reading these documents, Jess tries to piece together the story of Spanish imperial commerce in the early days of colonial Panama while emphasizing that mules were the protagonists. “They literally carried the Spanish imperial economy on their backs!”

In a few weeks, Jess will be back in Seattle. They will take a lot of impressions and experiences with them from their time in Seville: the feeling of walking through a city with many historical layers; unbundling old, dusty documents; and the excitement of finding traces of the Panama mules in the sources. Being physically at the archives where the documents have been held since the eighteenth century, Jess gained a sense of Spanish empire building. “It’s a funny thing to look at Spanish bureaucracy of the seventeenth century while navigating the Spanish bureaucracy of the twenty-first century.” After four months of exploration and research, Jess looks forward to coming back. "I really love Seville, and Andalucia in general has been an incredible place to learn about and explore. But in all honesty, I am in a rush to get home to Seattle to my three dogs and cat."