To the horror of many modern-day critics, J.R.R. Tolkien has several times been selected in national polls in the U.S. and Britain as the author of the twentieth century, beating out such worthy opponents as James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. The recent success of Peter Jackson’s film version of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien’s best-known work, has served to increase his popularity even further. This course takes on the challenge of understanding Tolkien in the context of the many different pasts he negotiated in the process of creating his complex mythology. Tolkien was first and foremost a philologist: what became Middle Earth had its origins in his habit of inventing complex language systems for which he then felt compelled to construct entire new worlds and populations. He was a medievalist, a specialist in the northern mythologies of early England, Scandinavia, and the Celtic lands; the heroes and monsters of those early tales fired his imagination from his earliest boyhood and continued to animate his scholarly and popular writing throughout his adult life. He was also a devout Catholic who combined complex Neo-Platonic theological notions of good and evil with the fatalism of the Germanic myths. But if Tolkien was a man of the past, he was also a person caught up in some of the most dramatic trends and events of his own day: the trench warfare of World War I, in which he lost two of his closest friends, the battle of the Somme, from which he was himself invalided out, and the various social and economic changes sweeping over his beloved land of England before and after World War II.

All of these aspects--combined with his popularity as an author, of course--make Tolkien an ideal figure through whom to introduce students to the importance of myth as a way of understanding the challenges we face as humans living in the modern world. Together we will explore the ways in which past and present come together in his work to produce some of the most memorable characters and settings of the twentieth century and, in the process, help to create the genre of historicized fantasy literature that remains so important to us today. What is often referred to broadly as medievalism is in fact a constellation of intellectual discoveries and trends that helped to shape not only Tolkien’s own work, but the work of contemporaries like C.S. Lewis (also an Oxford medievalist, Christian, fantasy writer, and World War I survivor), Charles Williams, George Orwell, and others. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the birth of Indo-European philology and comparative linguistics; the discovery and publication of some of the great classics of medieval literature (e.g. Beowulf); the production (often ab nihilo) of nationalist mythologies like the Finnish Kalevala, the Scottish Ossian and Fingal, and the Welsh Myrvian Archaeology; and vigorous debates over the relationship of fairy tales and myth to history. All of these intellectual movements and trends form the background to Tolkien’s own subcreations: The Hobbit, The Silmarillion (the work of his heart, but probably the least successful of his major works in terms of popular audience), and of course, his masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings.

The themes of this course are the subjects with which Tolkien and his contemporaries were so fruitfully preoccupied: the relationship between language and myth, religion and the existence of God, the origins and nature of good and evil, the possibility of heroism in an age of total warfare, the age of the machine and its impact on the environment. At issue also are the ways in which Tolkien and his work have been received and interpreted. Was he, as many have argued, a racist whose only terms of reference for the depiction of evil were black and white? Was he a sexist, unable to imagine women in positions of real independence? An ivory tower sort, complacently divorced from the realities of the world? How can one possibly explain the appeal of a work like The Lord of the Rings in an era of feminism and sexual liberation, racial integration, popular anti-war protests, and the rise of technology? These will be important issues for us as the class progresses.

The class will meet face-to-face unless some disaster intervenes to put us onto Zoom for a while. Most class meetings will take the form of a discussion of the assigned readings, but there will be some lectures as well, especially in the beginning.

Unfortunately, I am not able to take auditors or Access students in this class.

The following books are required for the class:

1) To be read before the course begins: J.R.R Tolkien, The Hobbit (any complete authorized edition)

2) To be read before the course begins: J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (any complete edition)

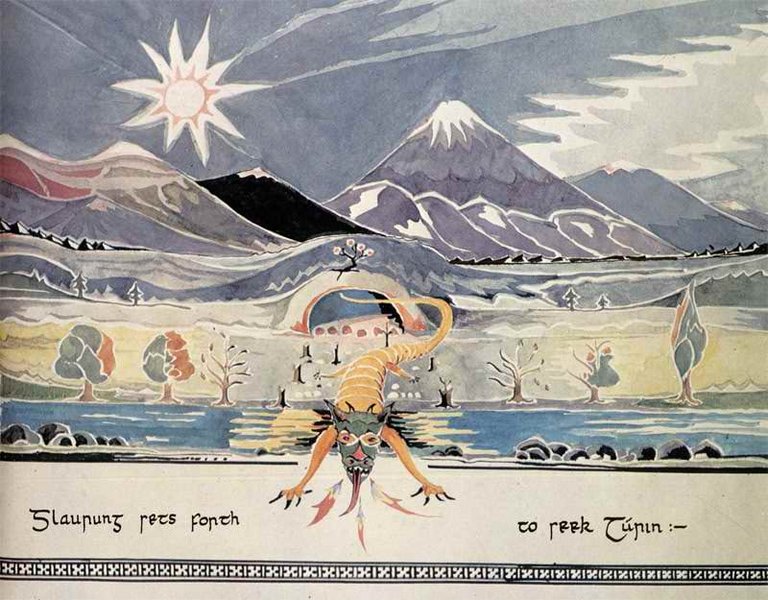

3) J.R.R. Tolkien/Christopher Tolkien, ed. The Silmarillion

4) J.R.R. Tolkien, The Tolkien Reader

5) Humphrey Carpenter, ed. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (abbrev. Letters below)

6) C.S. Lewis, Perelandra

7) J.R.R. Tolkien/Christopher Tolkien, ed., The Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-Earth (abbrev. Unfinished Tales below)

8) J.R.R. Tolkien, Smith of Wooton Major and Farmer Giles of Ham

Optional: J.R.R. Tolkien, The Children of Húrin

There are three written assignments due for this class: one midterm paper (5-7 pages) due February 1st, that asks you to put Tolkien's work into conversation with another war-time author of your choice); one final paper or creative project (c. 10-12 pages) due March 2nd, on a topic of your choice; and one final exam date TBA, but according to the University's time schedule. In addition, since the success of this class depends on student contributions, you will also be graded on participation.